Cyber Dialogue: A-UK-US heavyweights talk Russia’s invasion and cyber implications

The Ukraine-Russia war will be a “watershed moment” for cyber security, the future of the internet and the global economy. The short- and long-term impacts for governments and the private sector will be profound, even if it’s still too early to forecast what they’ll be. In this post, Associate Consultant Finn Robinsen reflects on the key messages from CyberCX’s latest Cyber Dialogue.

The Ukraine-Russia war is a major turning point in cyber history. This was the key message at emerging from CyberCX’s latest Cyber Dialogue, featuring three cyber heavyweights from Australia, the UK and the US:

- Ciaran Martin, formerly inaugural head of the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre and CyberCX Global Advisory Board member

- Admiral Michael Rogers (retired), former head of US Cyber Command and the National Security Agency and CyberCX Global Advisory Board member

- Alastair MacGibbon, CyberCX Chief Strategy Officer and former head of the Australian Cyber Security Centre

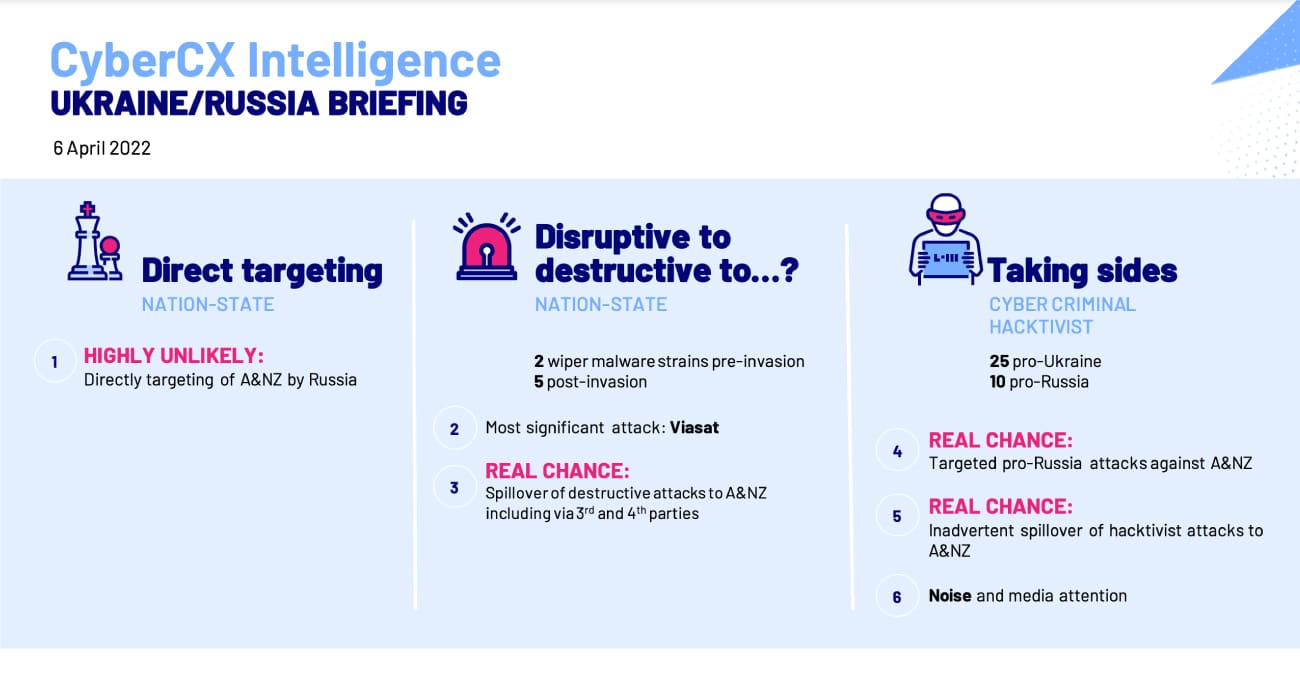

The Dialogue started with an intelligence brief from CyberCX Intelligence, with updates on the latest from the conflict and spill-over risks for Australia and New Zealand.

Don’t expect a ‘cyber Pearl Harbour’

Cyber attacks have been a constant in Russia’s treatment of Ukraine, since at least its first invasion of Ukraine in 2014. But so far, cyber attacks have not played as decisive a role in the war as some analysts predicted, given Russia’s status as one of the world’s most sophisticated cyber actors.

The panellists emphasised that cyber operations take time, effort and infrastructure. Martin also questioned whether Russia’s cyber commanders were as “unready” as the rest of Russia’s military forces and failed to adequately plan before the invasion.

“In grey zone times [before war] … the Russians will spend 18 to 30 months planning and executing these operations, but when you are actually invading a country, you can’t invade it with computers.”

– Ciaran Martin

But the lack of a crippling cyber onslaught on Ukraine may also reflect the strength of Ukraine’s defences. In Rogers’ view, the Ukrainians “are one focused and determined opponent.”

Non-state involvement is unprecedented, but isn’t offering decisive advantages

The most unique cyber characteristic of the war is the involvement of non-state groups.

Ukraine and Russia have benefitted from criminal ransomware groups, independent hacktivist collectives and cyber security companies to enhance their defensive and, in some cases, offensive capacities. As of April, the CyberCX Intelligence team is following 25 pro-Ukrainian non-state groups and 10 pro-Russian groups involved in the conflict.

“We have never had a cyber conflict before where we have had so many second and third parties who are now an active extension of the primary combatants.”

– Admiral Michael Rogers (ret’d)

But the panel highlighted the risks of mobilising non-state cyber groups to participate in a war. Rogers noted his concerns about “inadvertent escalation,” given these groups are not closely controlled by Russia or Ukraine, but instead have a broad licence to “cause harm.”

As to the effectiveness of these non-state groups, the panel agreed that most of their activities so far have been of low-intensity and minor consequence. However, it’s possible that the unprecedented call to digital arms is contributing to the wider “information war” between the countries.

MacGibbon observed that, so far in the war, “the information dimension of cyber has had much greater effect than cyber as a disruptive tool.” Martin suggested that Russia may rue leaving Ukraine’s internet access undisrupted, as Ukrainian Prime Minister Zelenskyy has used it to great effect garnering international support.

China will have a keen eye for learning from the conflict

Just as Western countries are seeking to learn lessons from Russia’s invasion, Chinese leaders are almost certainly watching.

“I think this conflict will be a watershed moment in the history of cyber war. I think the Chinese are really looking at this.”

– Admiral Michael Rogers (ret’d)

MacGibbon suspected Chinese strategic thinkers may be disappointed by Russia’s failure to be “more effective” with its cyber operations and will be thinking about how to improve their own command and control structures.

The panel also reflected that China will be keenly watching the successes and failures of non-state groups and crowdsourced cyber attacks in the war and considering how to further leverage its significant private sector cyber capabilities.

Australia and New Zealand, cyber crime is here to stay and it might intensify

The war in Ukraine could intensify the scale and destructive force behind cyber criminals, including for Australian and New Zealand organisations.

Martin suggested in the coming weeks and months that Russian President Vladimir Putin will want to use cyber operations to:

- cause economic harm to countries that have contributed to boycotts or put sanctions on Russia

- disrupt the unity of the 30+ country coalition that has supported Ukraine

- degrade the internal domestic cohesion of countries that have opposed Russia.

MacGibbon pointed out that Australian businesses wouldn’t need to be directly targeted to suffer harm, highlighting the risks of spill-over via digital supply chains.

Martin cautioned that, ultimately, the threat posed by cyber crime may escalate regardless of the outcome of the war. In both Russia and Ukraine, the economic and social costs of the war will be immense, which may prompt more citizens in both nations to turn to cyber crime to eke out a living.

The conflict may ‘balkanise’ the internet, but this might not be so bad

Ukraine’s successful global influence operation (and Russia’s reaction to it) could hasten the demise of a global internet. As Russia seeks to block itself off from Western platforms to gain greater control over its information environment, the internet will become increasingly fractured.

In MacGibbon’s view, a split between the free and open Western internet and more tightly controlled authoritarian cyberspaces might not be so bad. It could help insulate us from mis- and dis-information, while also assuring the integrity and safety of the broader technology stack.

“Russia will look to China for [critical technologies], and we should look away from China for our critical technologies.”

– Alastair MacGibbon

But while Russia can block out foreign platforms, it lacks the technical and consumer base to create its own internet. This is unlike China, which has made significant investments in building its domestic technology capabilities. Both Martin and Rogers emphasised that if Russia turns to China to collaborate on critical technology, this could dramatically alter global power balances and the future of technology.

Finn Robinsen, Associate Consultant

Guide to CyberCX Cyber Intelligence reporting language

CyberCX Cyber Intelligence uses probability estimates and confidence indicators to enable readers to take appropriate action based on our intelligence and assessments.

| Probability estimates – reflect our estimate of the likelihood an event or development occurs | ||||||

| Remote chance | Highly unlikely | Unlikely | Real chance | Likely | Highly likely | Almost certain |

| Less than 5% | 5-20% | 20-40% | 40-55% | 55-80% | 80-95% | 95% or higher |

Note, if we are unable to fully assess the likelihood of an event (for example, where information does not exist or is low-quality) we may use language like “may be” or “suggest”.

| Confidence levels – reflect the validity and accuracy of our assessments | ||

| Low confidence | Moderate confidence | High confidence |

| Assessment based on information that is not from a trusted source and/or that our analysts are unable to corroborate. | Assessment based on credible information that is not sufficiently corroborated, or that could be interpreted in various ways. | Assessment based on high-quality information that our analysts can corroborate from multiple, different sources. |